Seeing your curtains sway gently in response to the afternoon breeze is a romantic word picture, like watching the house breathe. Until I tell you there’s a storm outside, and the windows are shut. The horrifying reality is that the cold wind is inside the house with you.

Here’s some simple fixes I’m making this winter to stop the chill from breaking in via poorly-insulated windows.

It doesn’t matter how many solar panels you have on the roof or the performance of the reverse-cycle system keeping you warm this winter, letting all that heat seep out the window is such a waste. If you don’t have a battery, it means you’re drawing from the grid to stave off the cold as soon as the sun goes down.

If you wan to keep your bills down, then efficiency is always king.

Windows Suck

Yes, yes I know there’s some benefit to having natural light and a sunny outlook to improve your mood, but windows seriously suck energy: roughly 40% of your heating is lost out through the glass in fact.

And they suck energy in across summer too, with windows accounting for around 87% heat gained when it’s hot outside.

A single pane of bare glass can gain or lose up to 10 times more heat than the same-sized area of uninsulated wall.

Here’s the thing though: builders in Australia have realised windows are cheaper than walls. A square meter of leaky alloy frame and 3mm glass doesn’t cost as much as timber, insulation and bricks.

Hence, we the public are marketed novelty oversized windows, for breathtaking views of your neighbour’s grey fence. Windows that go right up to the eaves are fantastic, because a steel lintel to support more bricks is another expense builders can avoid.

Secondary glazing is pretty unobtrusive.

Leaky Describes Two Problems

Firstly, there is seepage.

Aluminium is cheap for durable window frames and also makes great cookware because it’s a brilliant conductor of heat.

When heat seeps through material from your comfortable space to the outside of the house (or vice versa), housing efficiency jargon calls this a thermal bridge. Windows are a thermal superhighway, ably supported by steel or aluminium structure.

High-performance windows that have been available overseas for decades use either uPVC plastic or thermally broken metal frames, where the metal on the outside isn’t connected to the metal on the inside.

Gentle encouragement is sometimes needed to make things fit.

Secondly, there are drafts.

Most aluminium windows slide to open, and they are an inherently bad design. What passes for seals is just a brush or a bit of fluff. There are gaps top and bottom to make the sliding window easy to remove. While the track at the bottom for the rollers literally has vent holes in it.

This staggered window in the bog, like a fixed louvre, could never be closed until now.

Why? Well a poorly insulated house can often have condensation on the inside of the windows, so these channels are designed to collect water and drain it outside the house.

In other words. Australians build crap houses, and then just make holes to let the water out.

Wooden windows aren’t as bad.

In the age of carbon fibre, I refer to wood as the original carbon composite. Not only does it look lovely, it doesn’t conduct heat, so provided you can keep the weather off the frames, they really are better than aluminium.

However, wooden sash windows, the ones that slide up and down, they suffer the same sorts of leaks.

Old Style Comfort Control

Before air conditioning was a thing, people built houses with high ceilings simply to store a comfortable temperature while the heat of the day passed. Warm air could sit overhead and wait until the evening, when you could open the place up and flush it out.

Sash windows are so often painted shut, people don’t realise the top pane is supposed to slide down. I can assure you from first-hand experience, opening the bottom window does less than half the job. Opening both windows and letting heat out the top is three times as effective.

Sealing Sashes

Timber swells and shrinks with the weather, so sash windows need a little bit of clearance and maybe some wax to make them slide nicely. These gaps mean poorly made windows want playing cards jammed in them to prevent rattles, but even beautiful carpentry will leak a lot of air.

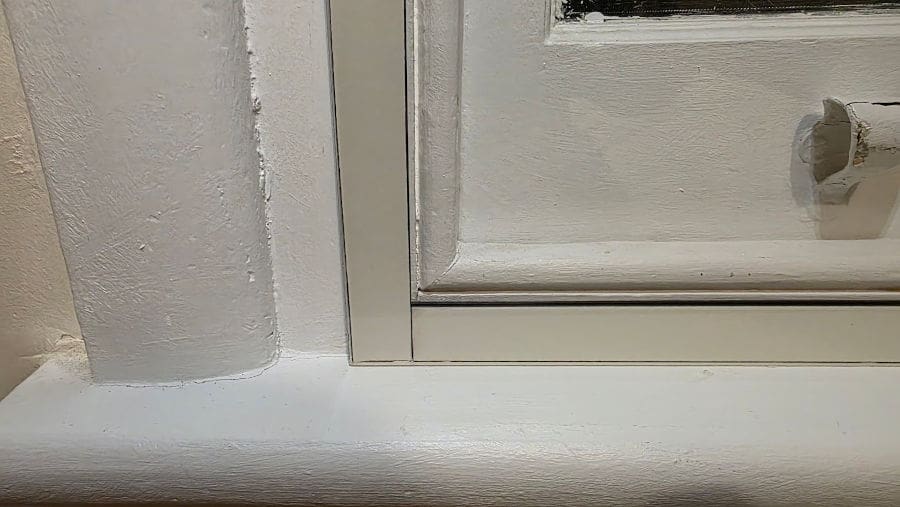

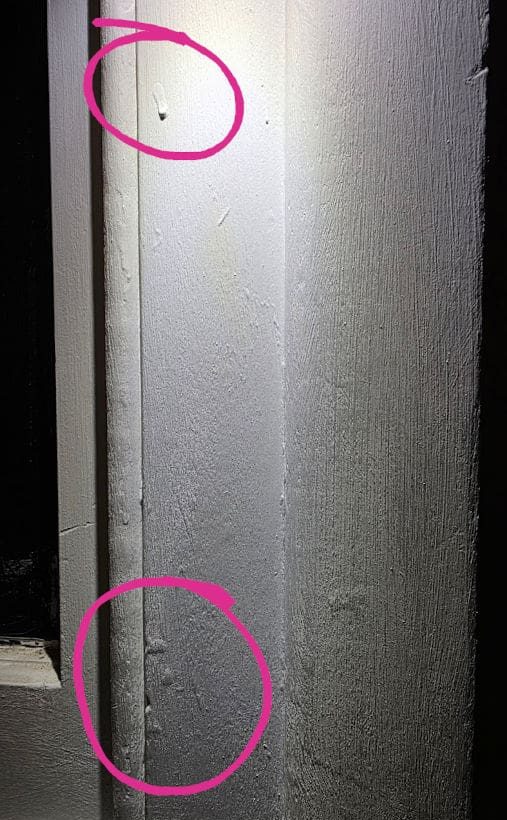

The step in this frame required filling with Sika 11FC sealant (highlighted) before the new pane and magnetic strip was offered up.

The internet doesn’t offer many detail shots of the finished product.

So while we’re going to install some new curtains and pelmets, I’ve set about using a slightly novel way to seal my sash windows using a single pane of 4.5mm perspex to stop the dreaded drafts.

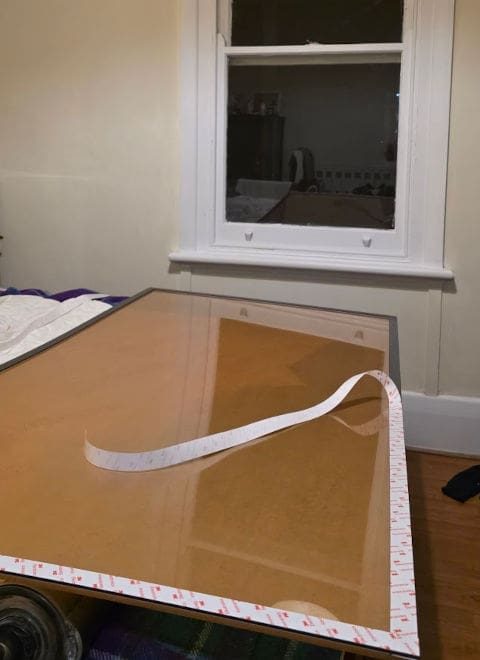

Peel off the backing tape and get ready to stick the new pane in place, then remove the protective paper film.

Magnetic Magic

There are commercial suppliers of magnetically fixed secondary glazing. They arguably offer a more aesthetic finish with colour-coded edges, but it’s a little expensive.

I’m beginning to appreciate that the price isn’t too bad though, considering the effort involved in learning, measuring, ordering, transporting and installing.

Site supervisor was nonplussed by the accurately sawn edge of the plastic. This is easily sanded smooth if you’re so inclined.

For my project I started out measuring 13 openings and ordering material from Menzel Plastics. Be aware that some suppliers will score and snap sheets but better ones saw them down to size.

I’ve also ordered 30 metres of magnetic strip. Type A has a white foam backing, which I chose to stick onto the perspex so it roughly matches the colour of the window frames.

Turns out this foam backing would likely be better on the slightly uneven timber window frame. My first practice run shows the type B magnetic strip doesn’t conform much, so the adhesive doesn’t stick very well in some places. Sikaflex 11FC fixes that though.

These little lumps need to be shaved off or sanded down

Lessons Learnt

It looks so quick and simple on EweTube but I’m happy to report on the details which might bring you unstuck.

Perhaps the most important point I can make is this; assume nothing. There’s every chance your builder made the window sill crooked in relation to everything else.

The gap arrowed doesn’t appear at the bottom of the 1.6metre tall pane because the window sill isn’t straight.

- Measure top and bottom – your window opening might be tapered

- Give yourself clearance – 5mm per metre for thermal expansion

- Make doubly sure the surface is clean and free of lumpy or loose landlord-spec paint

- See that the frame you’re sticking to doesn’t have any steps

- Maybe order the more adhesive strip next time

- Trial fit your new pane before removing backing tape

– Check handles or locks will clear

– Make sure everything is square - You’ll only get one chance to stick the landing

– Mark the frame or add some guides if need be

Stay Tuned

I’m going to do a few more improvements around here with fettling a hot water service, fitting an induction cooktop, fixing French doors, sorting draughty chimneys plus other gaping holes in the fabric of this building.

For this episode, I’m pretty pleased. The results don’t look terrible, and the room is already much quieter. We’ll report back if there’s any problems with condensation, but for now this looks like a real winner.

For more on winter-proofing your house, read the earlier pieces in this series covering some general tips, and on how to properly maintain your reverse-cycle system.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

Yeah, i can remember growing up in a Qlder in winter and freezing.

All the doors and windows were shut, but with the the westerly winds blowing, I would lay in bed at night and feel and my hair tossing about in the resulting breeze coming through all the gaps in the windows and single layer tongue and groove exterior wall.

Building crap houses in Australia is not a new thing!

Anthony, the real crime is that we are still building inefficient buildings in Australia. The ´average´ Aussie builder builds an ´average´ house that would not pass muster in many countries.

5>10% more cost during building would make huge savings over the life of the building. Leaks can be found (then rectified) with a Blower door test: a test that is mandatory in many countries. Mr Average Builder would quickly adapt to the need to build leak-free (Much easier to do it right first time!)

With a really tight building there needs to be an air exchange system. An MVHR system is incredibly efficient using less than 100W. The heat or cool in the building is saved by transferring to the incoming air. There are 2 other advantages: the incoming air is filtered, so dust buildup is reduced (less cleaning!), & clean air is introduced to the bedrooms & living areas, with the exhaust air taken from the Kitchen & bathrooms/laundry. This means polluted air from cooking & humidity are reduced.

Good article for people to sink their cold teeth into.

Having been in the glass industry for some 35 years, glazing in homes is certainly something more people are aware of now.

Building codes and in some cases council regulations on energy efficiency have made inroads with general knowledge on at least awareness.

Australia is in general a climate that doesn’t really NEED a lot of thought to regular regions in regards to glazing efficiency, but it certainly helps in the colder areas.

Double glazing / IGU’s (insulated glass units) into new homes, or during renos is becoming a lot more common now, and not as much a price barrier as it ha been in decades past.

Laminated glass, with it’s PVB interlayer helps insulate cold through glass, not overly expensive, but can be more difficult to update older frames made for thinner float glass.

cont . . .

Cheaper options ?

Acrylic sheet is very costly !!

Clear Coreflute from Bunnings is very cheap, the 8mm material is quote firm and of course the double flute if spaced from a window pane, that minimal gap yields an equivalent of triple glazing.

(The narrower the gap, the better for double glazing for insulation, for sound proofing a large gap is better.)

You can get thinner Coreflute, 3mm, but it is flimsier.

Most people would use this in a semi permanent state in a window sill area, or in some case it could be fixed so it allows windows to be opened.

Yes, secondary glazing on wooden windows and doors is easier than aluminium frames. I got away with a thin bead of silicone on several of mine. Been there 5 years now without falling out.

One tip for beginners is don’t buy the plastic and then put the job off for too long. The paper backing sheet sticks to the plastic and is a PITA to remove.

I think I got mine from Adelaide Plastics.

Apropos measurements, when ordering a replacement fly-wire door, they want height (left & right), width (top & bottom), *and* both diagonals. The latter are more than check figures, they get the lean right. A 60 yo timber framed house might have been sorta square back then, but the ground moves and things shift. By the fifth one, it’s a simple rhythm – and they fit.

Forty years ago, I glazed 8 clerestory windows with a clear double-walled polycarbonate, sold as an alternative to Laserlite. The long sheets could be cut with a fine-toothed crosscut handsaw. The 5 mm square hollows running the length, and filling the width, must have added insulation, but only admitted light. Sight was greatly blurred, but not a problem 4m up.

My new build had to have double glazing, but Al frames were cheaper. To reduce bridging, my ToDo lists says “Slit some left-over cedar to skin the frames inside with porous low-conductivity wood. It’ll look better too.”

But I need to clear the workshop first.

Thank you for your very helpful sharing of your experience Anthony.

Long time reader, first time poster.

Fantastic article – I second that.

Theres a lot of garbage on the internet but Anthony just hits the nail on the head with most of his articles. Keep up the great work

A problem is that different states have different regulations, and, in some states, regulations are designed to obstruct household energy efficiency.

I had sought a quote for replacing wooden framed windows (the type that swing out horizontally, so that, when they are fully open, anyone standing below them, who straightens upward, tends to hit the head on them) with sliding windows, and, the local glazier told me that I would need to get a builder to replace the window frames.

So, I have no idea of how many thousands of dollars, it would cost, to replace a 4′ by 3′ wooden double window, with a sliding window system; thence, how many thousand dollars, for each such window, to replace it with double glazing.

And, that is apart from the stupidly installed, and bodgy picture windows, up to about 8′ square.

Unfortunately, in Australia, building “standards” appear to have been organised by preschool children,. playing in sandpits, with the “standards” designed to be reckless.

The promoters of double glazing are excellent at marketing, but it is a product better suited to northern European conditions.

Often overlooked is low-emissivity glass (‘low e’ or ‘smart’ glass). I’ve used it twice now. On our most recent (large) house it cost $3,500 extra, including full sized sliding patio doors. Its very cheap for what you get. There is at least one Australian manufacturer (google EnergyTech).

I agree though that aluminium frames are the killer. But I guess they don’t rot or warp.

While it may be true that double glazing has excellent marketing, it is hard to deny how effective it has been for our Queensland house – particularly windows that are shield from direct sun.

Not only do they help keep heat out, but they make the A/C much more effective too.

The other major benefit is noise insulation. We effectively have a silent house when the windows are closed, which is very nice.

Unfortunately double-glazing is seen as a premium product in Australia and priced accordingly. Our European friends get much better pricing because it is a staple of the building industry. Point being, there is no fundamental reason why double-glazing has to be ridiculously expensive in Australia.

Great tips for keeping winter drafts out! We see firsthand how much energy is lost through poorly sealed windows. Simple fixes like weather stripping can significantly lower heating costs. Every bit of insulation helps—not just for comfort, but for smarter, more efficient energy use year-round.

Another consideration is to simply get rid of unnecessary opening windows. I live at the top of the Blue Mountains in a 70’s project home that had a huge number of awning windows. After living here for 10 years I realised that we never, ever opened half of them. So I’ve been gradually removing them and replacing with fixed double glazed units (luckily we have wooden window frames so DIY was an option). Makes a huge difference.

There’s one caveat, though: NCC Volume 1 requires openable windows or doors equivalent to at least 5% of floor area. On my OB it was easy to comply with one 2.4m wide fixed glazing, compensated by the adjacent exterior door.

My minimal (10% of floor area) total window area reduces heat loss, but that meant (50% – door area) had to be openable.

Window openings will have double studs either side, and a lintel above, so zero load on the window. There’s then only adequate weather flashing to worry about, I figure … and no 2mm gaps, for ember exclusion.

As window reveals are padded out between the studs with wood or plastic packing, it can be just as easy to fit an aluminium framed window, I’ve found. That does though suffer from thermal bridging, which is reduced with a wood frame.

I like the bubble wrap on window glass you mentioned in a previous issue; I’ve done this and hope it also keeps the heat out in summer.

Very little here on what can be done with existing aluminium windows. My house is full of them, most open by sliding horizontally with that brush ‘seal’ Anthony mentions (including big sliding glass doors), others are hopper windows with a winder closing mechanism, at least these have a rubber seal. I probably have to just suck it up but would appreciate understanding the available options.

To deal with the frame’s substantial thermal bridge, a few layers of strips of Les’ Coreflute would trap a wealth of insulating air, but doubtless require an aesthetic top layer to match the curtains. Wood veneer or self adhesive edging tape? Bunnings also has a green insulating board, which could perhaps be layered.

The imperfect airseal of sliding windows is maybe less problematic. My living area has 7.5 m² of double glass area in 5 windows, and 600 – 700W of RCAC keeps it at 24°C on cold nights. That’s despite aluminium frames, 50mm wide at the bottom, and sliding sashes. Admittedly, the 6-stars insulation efforts, necessary for the new build, do mean the ceiling and walls do their bit too.

And the indoor HWS means its heat loss is helping too. (Maybe 3 kWh/day, or more, judging by how much keeps going in even without hot water draw most of the day.) It takes so little out of the house battery that most nights I’m too lazy to light the wood heater.

Thanks for the ideas. Some work to do, then. Re the sliding windows, I can feel a slight draught at the edge with strong wind, but I think most of the heat loss is through the glass itself, you can feel the cold radiating from them. I also need to look at the ceiling insulation… thanks again.

Phil, you’d be right about the glass panes allowing heat / cold transfer.

Not much you can do apart form heavy drapes, pelmets to stop as much as possible.

Ssee if you can get your hands on an IR thermal camera, they are a few hundred $ to buy, or maybe someone you know has one you can borrow.

You can easily see cold spots on the ceiling, near windows and doors, glass etc, and get an idea of what to prioritise.

Single glazing was a frigid black-hole heat vacuum for me at just 200m altitude in the Dandenong ranges in winter, barely ameliorated by 8 tonnes of firewood p.a.. The quickest remedy there is floor length lined/double curtains with pelmets. With convective airflow blocked top & bottom, *and* radiative loss stopped as well, the difference is marked immediately. Blocking at the sides is easiest on a short wall – go from wall to wall. That should also attenuate/isolate smallish frigid leakage airgusts. Ceiling fans, especially on high ceilings, help – *after* the curtains.

For smaller windows, like my 1.2×1.2m units, insulating honeycomb blinds are made to measure to fit inside the reveals, sliding up or down. (I’ve seen them advertised in Renew magazine.) They can be single layer or double (for Tassie, perhaps). They can be translucent, for daytime use. I was going to buy some, but the double glazing is doing it so far – no blinds at all, here in the country.

Keep warm!

Yes, I suppose that timber frames can be good if you can keep the weather off them. But I’m fairly certain that bushfire building regulations in some areas stipulate using aluminium/metal frames on the outside of the windows.

I have a question if I may. We have a add on sunroom that came with this house, it has 4 very large glass windows with aluminium frames and under the windows is made from something that looks like cold room paneling they must have got cheap from somewhere so it would be hard to replace the windows I looked at double and triple glazed windows but they said they would be too heavy and thick for the current wall without completely rebuilding that part of room it was a very “handy” way they did it so very expensive to fix. Would electric shutter blinds on the outside, original glass windows in the middle and thick roll down blinds on the inside do anything to improve the situation in this room at all as we are putting these electric blinds all around the house anyway? It does have it’s own little fujitsu aircon that heats up the room very nicely and fast it just doesn’t hold the heat for very long or should I just save money on the blinds? I don’t expect miracles but just improvement.

Hi Greg,

Cool room panels are good insulation, they build whole houses with it and render the outside with acrylic membrane.

Anything you can do to prevent air flowing past the glass will help, be that shutters or blinds.

Honeycomb or cellular blinds are also another option.

What’s likely most valuable is if you search My Efficient Elelctric Home; I hate to recommend the Zuccerburg empire but

https://www.facebook.com/groups/MyEfficientElectricHome

MEEH has a great community of 140 000 like minded Australians who are ready and willing to offer ideas and valuable expertise on electrification.

Just don’t mention wood fires, they’ll shun you.