Participation in new energy services such as virtual power plants is building and consumers need better protection says the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC).

In the ACCC’s recently released thirteenth report relating to its inquiry into the National Electricity Market (NEM), new energy services are included for the first time.

Just briefly, a virtual power plant is generally a distributed network of solar and battery systems, with charging and discharging of batteries from and to the grid controlled by a central operator. Participants usually receive incentives for handing over some/all control of their battery. These can include sign-up payments, regular credits, better feed-in tariffs, discounts on mains electricity consumed or discounted/’free’ batteries (or a mix).

The ACCC report indicates 38,200 customers were participating in VPPs across New South Wales, South-East Queensland, Victoria and South Australia as at January this year; increasing at an average rate of 21.9% every six months in the two and a half years to January 2025.

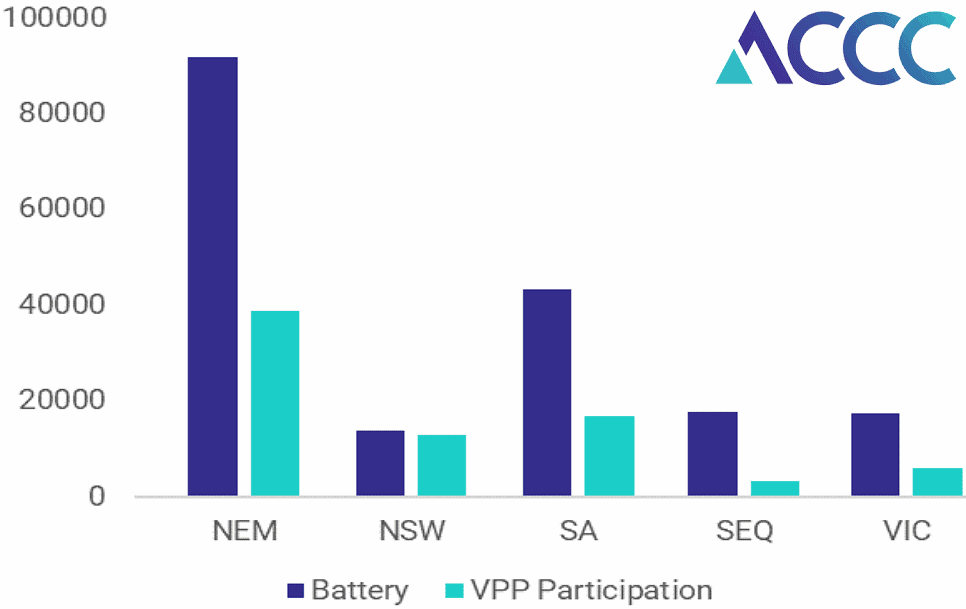

In most states, VPP uptake had still lagged well behind battery installations as at January 2 this year. Here’s the ACCC’s comparison of battery installations and virtual power plant participation rates by region.

The result for New South Wales is a head-scratcher, but the ACCC suggests this may be due to the NSW Government’s VPP subsidy for customers. But even with the incentive, the proportion still seems incredibly high.

It’s worth noting the ACCC’s figures are based on the Australian Energy Market Operator’s (AEMO’s) distributed energy resource register, which is a voluntary database of information about devices installed in the NEM. While representing “a large proportion” of batteries installed, not all are accounted for.

As for why elsewhere consumers are holding back, the ACCC’s research suggests:

- Complexity of VPPs.

- Reduced consumer control.

- A lack of familiarity with Virtual Power Plants.

Healthy Competition Among VPPs

The report indicates steady growth and signs of healthy competition among VPP providers, and that smaller retailers and non-traditional energy providers supply more than three-quarters of virtual power plant customers. To see programs compared side-by-side, check out the SolarQuotes VPP comparison table.

Hammering Batteries An Exception Rather Than The Rule?

One of the concerns consumers have about joining a VPP is how aggressively the operator will discharge/charge their battery to/from the grid, and when. For example, we’ve seen VPP customer reports of operators discharging much of a home battery in the late afternoon and evenings, leaving those households exposed to high mains grid electricity prices. But the ACCC report says:

“… the average amount of electricity dispatched into the grid per customer per year has remained reasonably steady at around 16 kWh over the three years to 2023—24.”

This was another figure I found surprising as I thought it would be much more.

Comparing Electricity Bills

The report indicates the following annual median electricity bill (without rebates) in 2023 to 2024:

- Regular users: $1,565

- Households with solar panels: $1,279

- Households with solar and battery: $936

- Households connected to a VPP: $580

Some VPP Offers Riskier Than Others

The ACCC notes elevated risk for some VPP products. Lengthy contract terms and potentially large exit fees may exist where the VPP involves financing on solar panels and/or batteries, and households hosting provider-owned resources. The lowest risk was associated with ‘bring your own battery’ programs.

More Protections For Consumers Recommended

The ACCC says in order to achieve the maximum level of energy market participation by consumers, including engaging with new services such as Virtual Power Plants, there should be specific consumer protections compelling energy service providers to:

- Ensure consumers are no worse off and are fairly rewarded for their participation.

- Protect the energy asset investments of consumers.

- Put guardrails in place, such as limits to the level of external control that can be exercised.

- Design and distribute energy offers with a focus on the consumer.

The report identifies a number of challenges for consumers and offers insights that could support or inform amendments to the energy-specific consumer protection framework — which is primarily the National Energy Customer Framework (NECF) that operates alongside the Australian Consumer Law (ACL).

Not Just About Virtual Power Plants

There’s much more in the report concerning Virtual Power Plants and other new energy services including electric vehicle tariffs and behavioural demand response; plus all the Commission’s usual reporting.

If you have time on your hands and packed a cut lunch, you can read the 173-page Inquiry into the National Electricity Market report – July 2025 here.

Given how much has changed since the period this report covers — particularly with the launch of the Cheaper Home Batteries program and increased awareness of VPPs in recent months — the next couple of reports if made publicly available will be interesting; and they will be the final ones for the Inquiry.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

Isn’t the Western Australian state government battery subsidy scam requirement to join a VPP, a restrictive trading practice, outlawed by the Trade Practices Act, and, thence, isn’t any company that is involved in such a VPP, a beneficiary of , and thence, complicit in, the restrictive trading practice, thence being the equivalent of receiving benefits from crime?

What is the ACCC intending to do about that, or, does the ACCC only attack weak prey?

The next big thing I feel is Bi-directional EVs, & VPPs. For vehicles parked during the day on a Bi-charger, there is the possibility of charging off the grid 12>2pm approx (Free Energy time), then reselling later in the day.

My current problem with connecting to a VPP is I have a Zenaji batt connected to a Victron MP2. This is controlled by Home Assistant so there may be a time when an interface to VPP is written.

Hopefully, Bi-EV with OCPP compatibility may enable connection to a VPP.

I can’t find any VPP offering that ticks my two boxes: 1) A guarantee they won’t cycle for a return less than the LCoS of the battery (about 15c/kWh on a subsidised battery these days); and 2) They will cut you in on the booty from a Market Price Cap event.

Amber’s Smart Shift quasi-VPP comes very close, but I choose to stay in control and do my trades manually on Amber (but you have to enjoy the game of it and they don’t make it as easy as they could).

A battery should be able to make money (in the peakier priced states and if your net generation exceeds net usage, at least) and for my sums, a 5 year payback relies on those earnings.

If we include the possibility that gentailer-VPPs will marshall home BESS into their dodgy price-spike bidding shenanigans, I just can’t find the good in them.

Yep, when I get my new battery & join you on Amber, I’d love to start an Amber user group advocating for an economic and a carbon optimiser mode in addition to their current modes.

In both modes the user would provide LCOE for the solar and LCoS for their battery and and required profit margin and Amber would only export when the profit margin is exceeded. In economic mode the cheaper of grid cost and battery export cost will determine battery usage. In carbon mode, the carbon intensity will be the deciding factor in choosing between battery discharge or use of grid power.

Feel free to start the campaign before I join!

I signed up to the Shinehub VPP through Mitcham Council in SA and had battery installed in April 2024. In 16 months since I’ve not had a single VPP event.

Make sure you question the council VPP partners hard – ShineHub for example still don’t appear to have their latest battery supplier, Hinen, working properly with the VPP, or with their own Powow monitoring app (at least on my installation anyway). Is nice having a battery and love the concept of a VPP but without decent monitoring or a working VPP integration i would have been better off going it alone and not tying myself to their battery.

Hi KJ,

Bulk buy schemes always seem to favour chintzy companies offering cheap gear with less than stellar subcontractors. I don’t know why Mitcham Council, known for the “its ours and it’s paid for” bumper stickers (designed to discourage through traffic from the unwashed southern suburbs) decided their demographic was a cheap one.