Are Smart Meters Worth Getting?

Got an old analog electricity meter? These days, having any major electrical work will come with almost 100% certainty it will be replaced with a smart meter. Major work includes getting solar and/or a battery installed.

If you don’t want a smart meter, you’re kind of out of luck, as the plan is for all homes to have them. On the 28th of November last year, the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) finalised rules requiring universal smart meter adoption by 2030. The only state not covered is WA, but roughly 90% of homes already have one there, so expect smart meters to be universal or real close to it in four years’ time.

The accelerated rollout isn’t just because the AEMC is aiming to unlock the achievement for 100% smart meter penetration — so they say. The official goal is to lower costs. This is mostly achieved through smart meters allowing households to use electricity tariffs that improve grid efficiency. An example is the Solar Sharer Offer that requires electricity retailers to offer plans with three or more hours of free daytime electricity from July in NSW, SE QLD, and SA. If you want to take advantage of this and don’t have a smart meter yet, you may want to request one soon, because demand will be huge.

However, not everyone wants a smart meter. To reduce resistance to the rollout, the AEMC has spent the past couple of years ensuring people will still be able to use a flat tariff after getting one. This is a change from a few years ago, when some people were kicked off flat tariffs against their will — sometimes without notice — when their meters were changed. It took them a while to work it out, but the AEMC eventually realised that if they let electricity retailers hit people with a stick when they did what the AMEC wants, people would be less likely to do it.

Because smart meters reduce grid costs, you might think you’d be paid to get one, or they’d at least be free. But, strangely enough, it doesn’t work that way. If you have work done that requires a meter changeover or request a meter change, you can be hit with charges. They’re normally not too bad, as you don’t have to pay the full cost, but if there are complicating factors, such as asbestos in your switchboard, it can get very expensive.

This is an old analog “spinning disk” electricity meter. If you have one of these, you don’t have a smart meter.

Smart Meter Penetration

Here are the percentages of homes with smart meters already installed, from highest to lowest. It shows every state and the only two territories most people have Heard of. The figures with decimal points are precise and provided by the AEMC on the 28th of November, while ones for WA and the NT are estimates:

- VIC 99.12%

- WA ~90%

- TAS 78.06%

- NT ~50%

- SA 46.49%

- QLD 42.63%

- ACT 40.27%

- NSW 39.17%

If you’re in VIC, WA, or TAS, chances are you already have a smart meter, while everywhere else the odds are around 50/50 or less. However, if you have a solar system that isn’t elderly, you’re much more likely to have one, and if you have a home battery, you definitely should have one.

In several states, a hell of a lot of meters will have to be installed over the next four years to get to 99+% coverage. Without the AEMC pushing the accelerated rollout, it would have taken until around 2036 for smart meters to become universal in QLD and 2037 in NSW. In SA it wouldn’t have happened until 2041.

This big boy is an EDMI Atlas Mk10D 3-phase smart meter. If your home has 3-phase power, it will need a 3-phase smart meter and these are larger than the more common single-phase smart meters. “Activestream” is the meter service that installed it.

How Can I Tell If I Have A Smart Meter?

If your smart meter has a spinning disk and mechanical dials, it’s not a smart meter. If it looks like the picture immediately above or one of the pictures below, then it is a smart meter. If it doesn’t look the same as the smart meter pictures but has a digital screen, it’s probably a smart meter, but could be an older interval meter. These work like a smart meter as far as your bills are concerned, but can’t be read or reconfigured remotely.

A smart meter may have a short antenna on the side, but in towns and cities, it’s usually internal thanks to good mobile phone reception.

If you’re not sure what you have, the easiest way to check is to run an internet search on your meter’s model number and see what comes up.

You can also just look at your bill. If you have a time-of-use or a demand tariff, you almost certainly have a smart meter — or at least an interval meter. If it says “remotely read” or “type 4 metering” it’s a smart meter. And if it says “smart meter” that’s a dead giveaway.

If you’re still unsure, as a last resort, you can ring up your electricity retailer and ask them.

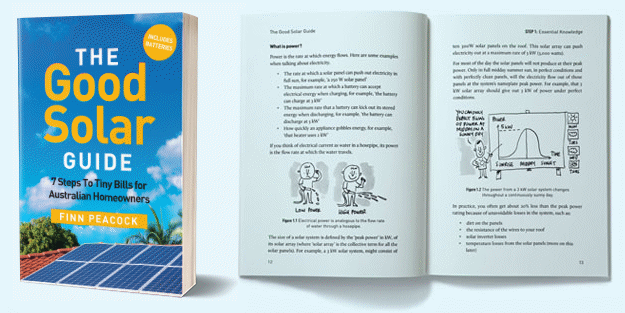

This is a Landis+Gyr E355 single-phase smart meter. It’s smaller than a 3-phase meter, but, despite this, I still don’t recommend trying to swallow it.

Why Smart Meters?

Smart meters do two things dumb ones don’t:

- Record when grid electricity is used and not just how much. They also do this for solar or battery electricity exported to the grid.

- Transmit and receive information through the mobile phone network, allowing for remote reads, connections, disconnections, and reconfigurations.

This gives them several advantages:

- No one has to be paid to be physically present to read the meter or do connections and disconnections.

- It allows electricity plans with time-of-use or demand tariffs that encourage electricity consumption when it’s cheap for the grid to provide power and discourage consumption when it’s expensive.

- Battery households can join Virtual Power Plants (VPPs).

- Households can use smart meters to get information on their electricity consumption patterns.

AEMC says the accelerated smart meter rollout will save around $507 million. They don’t give a figure per smart meter, but very roughly, they may lower overall annual costs by around $60 per household — before any benefits from joining VPPs are considered. With around 11 million grid-connected households in the country, that’s $660 million in savings per year. Enough to double Medicare-provided MRIs or provide every child in the world under five with a cigarette.

While these savings seem big, a considerable portion results from past rule changes that increased the cost of reading meters and operating the grid. So while smart meters do reduce costs overall, the large headline savings would be less if we were starting from the position of a competently run grid.

Smart Meter NEM12 Files

Households can use smart meters to get information on their electricity consumption patterns by having their electricity retailer send them an NEM12 file containing half-hour electricity consumption/export details. Details on how to do this are here. If you’ve had a smart meter for at least a year, you can use your NEM12 file with our Battery Calculator Tool to work out how much a home battery could have saved you.

This is another Landis+Gyr single-phase smart meter, but an older E350 model installed by a different metering service. Also, the tilt indicates that the photographer may have been slightly drunk.

Smart Meters & Tariffs

In the past, the only electricity tariff available to households was a flat tariff, which charges the same amount per kilowatt-hour (kWh) no matter when it’s used. Nothing else was possible because old electricity meters only knew how to count and couldn’t tell time. But smart meters allow time-of-use and demand tariffs. Each tariff has characteristics which can make it more suitable for certain circumstances — except demand tariffs, which are usually pretty crap overall.

Flat tariffs: These can suit solar only homes because they usually draw most of their grid electricity in late afternoon and evening when prices on other tariffs are high. But if evening consumption is low, they could still be better off on a time-use-tariff, particularly if their solar system is small.

Time-of-Use tariffs: These have higher rates during periods when electricity is usually expensive for the grid to supply, such as the evening, and lower rates when it’s usually cheap to supply, such as the middle of the day. They’re normally best for battery households, as they can get through the expensive peak periods using battery power. Plans with periods of free electricity are time-of-use. This includes Solar Sharer Offer plans with three or more hours of free daytime electricity, which will be available in NSW, SA, and SE QLD from July.

Demand tariffs: Instead of charging more per kilowatt-hour used during peak periods, these tariffs have a demand charge based on the highest average power draw over half an hour during a peak period. The highest charge in a month is then typically applied to every day of the month, which can make it pretty hefty. Demand tariffs may suit some battery households, but because one mistake or one visiting auntie who cranks up power consumption at the wrong time can be very expensive, I only recommend them for those who are confident they’ll come out ahead compared to a time-of-use tariff.

We’re now back to the EDMI smart meters. This is an Atlas Mk7A single-phase. Judging by the tilt, either the photographer was a bit drunk or the installer was very drunk.

How To Get A Smart Meter

There are three ways to get your old analog meter replaced with a smart one:

- Your electricity retailer decides they want to replace it and sends a letter saying so.

- Have major electrical work done, such as getting solar and/or a battery installed.

- Contact your electricity retailer and request a changeover.

The good news is the first one is free, but the bad news is it could still be years before they get around to you, as 2030 is still a long way off.

With the other two options you could be hit with fees. Usually, they’re not too bad and come to under $150 for most Australians. But make sure you’re clear on the amount to avoid an unpleasant surprise. While having to pay anything at all isn’t great, if it lets you use three hours of free electricity to charge a battery, an EV, or even just run an electric hot water system, it could be well worth it.

It is also worth remembering that the introduction of free daytime electricity will be capped, as we recently covered.

There’s a bit of misinformation floating around about supposed smart meter harms – subscribe to our free newsletter to make sure you get my follow-up piece next week on why the people making these claims are nuttier than a lumpy chocolate bar.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

I have a smart meter and stayed on a flat tariff plan.

I wonder if you will be able to keep the flat tariff plan and still get access to a 3 hours free plan.

It shouldn’t be an issue for the metering system, it depends on how smart the government is setting things up (not holding my breathe there, with the recent history of backflips and modifications to the home battery scheme and this scheme already), it will probably more depend on how much the power company wants to gouge you i suppose.

Time will tell no doubt.!

I got a smart meter and kept my flat rate. Unfortunately I was also required to go into a demand tariff at the same time to keep that flat rate. When I rang them to get a ‘please explain’ I got the usual run around of how this was a distributor requirement to have either a flat+demand or TOU. Whatever. Shouldn’t need a focus group for the regulators/retailers to figure out how not to stuff things up, but for smart people they do obvious dumb things at times

Be careful: the peak might cost you all month. If you have a battery, the battery should trim the peak but it does depend on setup.

Remember, items such as induction cookers & old non-inverter driven motors can have high peak power, so that few seconds might cost you the whole month.

ouch!

I was fortunate in that it wasn’t long after the TV media were flogging AGL over the moving people to smart meters and demand tariffs, and they caved on doing it.

So i just went over with my existing conditions, being flat rate and off peak

I was with OVO Free 3 with flat rate in 24 and 25, late last year switched to Globird Zero Hero which is technically a ToU. No demand tariff though, and hope not as it destroys the premise of free hours.

Ronald,

the ability to direct read the meter for the consumer was not mentioned. In SA & Vic, it is possible to read many smart meters with a special Zigbee dongle: the Rainforest one:

https://www.rainforestautomation.com/rfa-z114-eagle-200-2/

This dongle allows programs such as Home Assistant to get real time data.

(There was a home display available too, but possibly nla.)

Unfortunately, in NSW & Qld the govts were not smart enough to open the metering interface, so those residents need to wait until 2028 when an open

interface is mandated. I researched this because I wanted to direct read my

meter. btw, it is likely that NSW metering is fitted with a Zigbee i/f that is not enabled: the reality is it is not economical to build ´special´ models for small

markets, so the hardware is often fully implemented but not firmware enabled. Possibly this may be enabled in the future if available.

The NSW Endeavor link in the referred links to get NEM12 data, does not work. A search of Endeavor web site provides a page with a form that does not work. Endeavor must be stuck in 1987…..

Try this for Endeavour. It works for me at the moment:

https://www.endeavourenergy.com.au/for-your-home/energy-use-and-bills/meter-form

Ronald,

Apropos your comment about a competently run network, I can’t help but notice that the Solar Sharer Offer rollout, which requires a smartmeter, is restricted to the states which have the least smartmeters, so excludes all the states with the high level of smartmeters which would have facilitated the rollout. (With a minimum of shouting and arm-waving.)

If the decision makers didn’t just have their copy of the table upside down, then is their cunning plan to prod delinquent states to up their game, and find their way into the 21st century?

Expeditious rollout to prosumers seems a secondary consideration.

I think in this case, the explanation is as simple as these are the regions for which the AER determines a DMO eg it’s just SEQ and not all of Qld. The 3-free hours will be part of the DMO.

I think Vic immediately decided they’d do their own version as part of their VDO.

Love your posts Erik, sometimes I don’t even get to the end of them coz I feel I’m just reading my own thoughts :-).

At the moment I’m writing this solar farms are being curtailed here in SA due to high solar output. This can also happen in QLD. Yesterday, while I don’t think there was much curtailing, solar and a little wind supplied 90% of demand in NSW in the middle of the day. Victoria and especially Tasmania just don’t have as much solar gen around noon – but they will get there and it won’t take long.

WA is really off doing its own thing, but with their ~90% smart meter penetration they can keep cranking down the price of daytime electricity on their Midday Saver plan and encourage daytime electricity consumption that way.

Thanks for clarifying all that, Ronald.

I had mistakenly assumed they were called smarts-meters because of the sharp, stinging pain your budget will feel once you’ve had one installed.

Actually, that’s not true. I love my smart meter, and I believe they are both the source and the remedy for evening-peak bill shock.

As for demand charges — just let Auntie know we can’t afford any more visits and blame it on the smart meter — another pro for getting one installed.

Smart meters are evil things, everyone I know who has one says their electricity bills have skyrocketed..I understand that all grid customers willbe inflicted with these disasters in due course and the only winners will be the parasitic retailers.. There is only one solution, complete autonomy. If one chooses to keep a grid connection for redundancy it is critical to NEVER use any grid power when the bloodsuckers can gouge. Personally I would prefer to disconnect completely although I believe governments will still permit access charges. The ‘free’ power inducement is a scam since it only applies for a very short window and consumers can only gain a trivial benefit while the bloodsuckers profiteer massively.

Yes Doug, the ‘three free’ plan retailers will offer will be offset by higher shoulder and peak tariffs, and likely higher daily supply charge no doubt.

They will only have to offer 1 plan with the free hours, so people will have a choice.

They won’t want to reduce profit though, that is a certainty.

I now have negative bills. My smart meter supports solar + battery. Amber is my provider and i buy and sell wholesale with curtailment and even livev esponse choices.

Without a smart meter amber timeshift cant be connected

Dave in Gympie. We were conned into “Smart Meters” about a year ago & our monthly bill was about the same as our Quartey bill. We have now gone Solar with battery & looking to totally off grid.

Hi Dave,

Going off grid really isn’t a brilliant idea.

https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/off-grid-in-suburbs/

I had an interesting conversation with my solar installer when i had my battery upgraded a couple of weeks ago. He told me i probably had enough battery now to go off grid if i wanted to.

I told him I like the security of the grid being available if there is an issue, although i dont like bleeding from the eyeballs to pay for it in daily connection fees.

He told me it only takes about half an hour to get your grid electricity turned back on if you do have an issue.

I found that quite interesting. It really changes the paradigm around going off grid in the suburbs.

I’m still to conservative to give it a go though!

Hi Andrew,

One of the reasons people hate “smart” meters is that the retailers/bastards dont have to send a DNSP line crew, they can switch the power off remotely when you don’t pay your bill.

However they can switch it on easily too, provided the call center is open & everything works as it should.

Fundamental advantage is that mains power probs up your system and means the inverter doesn’t have to cope with spikes in demand.

Nor do you have issues with frequency shift in an AC coupled system.

I was disappointed when Victoria replaced my old meter with a smart one I used to like watching the disc go backwards with the excess solar !!

I am based in Melbourne and currently have a 30-minute smart meter installed with solar and battery. I’ have read that 5-minute interval smart meters are available. Can anyone confirm whether my existing meter can be upgraded or reconfigured to record usage in 5-minute intervals? Additionally, is Zigbee or other real-time communication supported on my meter (or available if upgraded), so I can access data for home energy management systems?

Sath,

as I mentioned above, in order to access faster (ie real time) meter data, you must have a local method of reading the data direct from the meter. The only way I know of achieving that goal (in Vic & SA) would be to use the Rainforest zigbee interface. this would need to interface by zigbee to a local computer. If you want this data for energy control, one option is to use a microcomputer (such as an Intel NUC, or the Home Assistant Green hardware, or similar).

If you are interested in this option, the first thing would be to enquire if your meter is zigbee enabled. (the meter does not talk standard zigbee, hence the Rainforest i/f: note made in Canada: not the dreaded US or other war-like countries!) https://www.rainforestautomation.com/rfa-z114-eagle-200-utility/

fyi, the Energy Retailer gets faster data, but only gives customer access at 30min intervals: as you said, pretty useless for real time control. Even 5 min data is too slow.

There is only one worthwhile response to the never-ending shenanigans of electricity retailers and that is opting out of the racket..These companies can staff offices with hundreds of muppets dedicated to creation of new ways to gouge customers. Smart meters, a few hours ‘free’ power, and TOU are simply the latest tricks conceived to rip off users. Personally I don’t have the time or the inclination to play their moronic games. Offgrid systems give ME total control and thats the way I like it.

2 things Doug: if everyone went off grid the grid would not work: VPP batteries are required in this modern grid. The second is that if too many go off-grid, the state may charge a connection fee anyway (much like the sewer/water charge).

The advantage of being on the grid is there is this huge virtual battery that covers the times that the sun does not shine. To me, worth $60/month for the security atm.

VPP is IMO a scam …. I refuse ro give proven parasites control of and exploit an asset I paid for. The grubs only interest is advantaging themselves at the cost of customers. I fully expect a connectuon, or rather an access charge, in fact I’m surprised that hasn’t been applied already. If / when it is, I for one will be making a LOT of noise about unreliabiliry since the grid falls over on average 3 times every week (remote area / ancient infrasrructure / zillions of trees). It would be more cost-effective for the parasites to keep out of my hair than to fix the infrastrucrure.

Wow Doug.

I get the impression that you don’t like them. LOL 🙂

How about just going off grid…

100% offgrid is the plan when my present 59c FiT finishes.I don’t trust any retail bloodsucker to change its spots and stop gouging.

Doug mightn’t be too happy when his inverter invariably fails and it takes a couple of weeks to get it going again or a new one.

Just a thought !!

Have to go back on grid !!

Or buy a generator

interesting enough, i was talking to my installer about this the other day after he just finished upgrading my battery.

He said i could just about go off grid with my big battery, I said i liked the “backup of the grid” being available in case of something going wrong.

He said something very interesting, he said if your powerline etc is still there, it generally takes less than half an hour to get the electricity turned on, just ring a retailer and tell them you moved in and forgot to get the power put on first.

Food for thought.

This isnt always the case. My amber VPP is completely unlike others. I am on wholesale. I have control plus amber smart shift does 85% of the work

I was prepared to talk with an intelligent lifeform at Amber (if indeed there is one) … made multiple attempts ro get in contact but nobody returned my calls. That is an immediate deal breaker.

I feel there is a possibility in the long term that we may be able to pay a connection fee, then separately contract for energy needs: This may be with a peer-to-peer provider (such as Amber), or we may be able to sell on the wholesale market directly in some form (risky).

It is difficult to design a system that NEVER needs external power input which may be caused by low personal energy generation, or more commonly equipment failure.

I feel it would be nice to be able to pay the connection fee directly with no retail markup. This might be by the energy retailer charging a small handling fee only perhaps. It definitely would stop energy retailers manipulating the connection fees with regard to energy prices.

Ronald,

Are you suggesting consumers opting for the 3 hours of “free” electricity will be left on their current rate/s except 3 hours in the middle of the day will be free?

Surely not!

From past experience the electricity companies are masters of “robbing Peter to pay Paul”. Invariably if you find a supplier who offers a fantastic Feed-in Tariff, you can be certain their usage charges will ensure your bill is much the same. This has been the case for at least the past 15 years or so. Compare various “competitive” rates, and usually the final difference to your quarterly bill makes it not worthwhile to muck around moving suppliers.

If a customer can’t transfer heavy usage virtually EVERY day (e.g. charging an EV), it is probably highly unlikely the electricity supplier will be charging rates that leave it any worse off. Much like ToU at the moment.

Or are you suggesting suppliers will be given a genuine “charges will remain the same, but we’ll give you 3 hours free”?

It will definitely be a good idea to check that plans with periods of free daytime electricity are worthwhile and don’t screw you over in some way in return for that free power. But here in South Australia it usually costs the grid nothing to supply an extra kWh of electricity in the middle of the day. By getting people to shift consumption to the middle of the day, or charge batteries, it can reduce grid costs in the evening. So there is clear potential for these plans to not screw over people in other ways – or at least not too badly. Now, I’m not so sure how well NSW will handle it as they have less solar per person, but solar is growing. We’re not about to say, “Yep, 49% coal is just right, stop it with the PV!”

In response to the claim that going completely offgrid doesn’t make sense, IMO offgrid is the ONLY way to get reliable power (we get three outages every week), its the ONLY way to put an ebd to the never-ending predatory financial shenanigans of retail bloodsuckers, PLUS it gives me the ability to tell the parasites to go do something physically impossible. All that aside, I am aware that many if not most offgrid installations are toys and their owners are clueless. I am most definitely NOT in that situation ..I have an industrial sized offgrid system with multiple backups, and I have infinitely more contempt for the establishment than any other inhabitant of planet earth. With this in mind I would not be living up to my beliefs if I supported the grid electricity racket.

Hi Doug,

Grid electricity is bound by law to be 99.998% reliable. Just that last 8 costs a lot of money.

If it goes off 156 times per year as you claim, then at 5 seconds each your DNSP has a case to answer.

The thing is that as more renewables are deployed, the grid gets more reliable. Being connected puts us all in this together.

I agree the “market” is broken and arguably the entire retail sector is redundant. It should be nationalised.

A reliable remote area power system needs to be about 4 times bigger and 5 times more expensive than a well built grid hybrid.

Unless you can build it yourself and maintain it as required by law (& insurance) then going off grid is just cost prohibitive & incredibly inefficient.

Your mileage may vary of course.

Regardless of legislation requiring a certain level of reliability, there is no way of enforcing that. Anyone who believes everyone is equal under the law is hopelessly deluded. Wholesale and retail power companies are comparable to politicians / bureaucrats / judiciary … effectively immune to law that masses are compelled to observe. The grid has been unreliable in my area for at least 15 years and clearly there is no penalty for the bloodsuckers. As for nationalization, no essential service should wver have been privatized, especially when the REAL motivation was avoidance of responsibility by corrupt politicians. Needless to say, accountability has never been on their agenda.